ACS Multimedia Atlas of Surgery: Liver Surgery Volume

Editors: Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS; David A. Geller, MD, FACS

| Product Details | |

| Year Produced: | 2014 |

| Pages: | 397 |

| Dimensions: | 8.75x11.15 in |

| ISBN: | 978-0-9846699-6-7 |

Includes book with full online access to all chapters. Price includes shipping costs.

For assistance, comments, or questions, contact Olivier Petinaux, Senior Manager, Distance Education and E-Learning, elearning@facs.org or call us at 1-866-475-4696

The American College of Surgeons Division of Education and Ciné-Med have developed the interactive Multimedia Atlas of Surgery: Liver Surgery Volume.

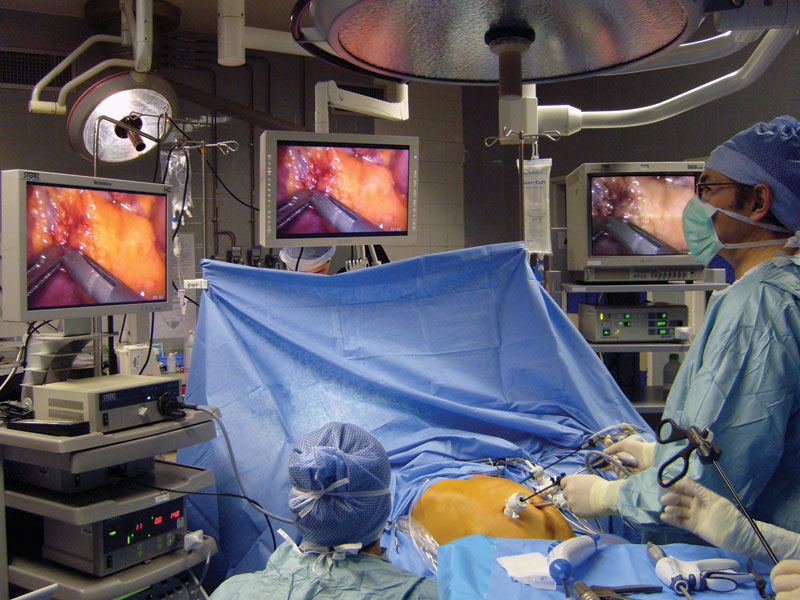

A comprehensive atlas style text, this volume includes 41 chapters presenting hepatobiliary repair techniques using open and laparoscopic methods. Expert surgeons provide detailed, step-by-step instruction using a combination of video, illustration, and intraoperative photos to clarify specific points of the procedure.

The text opens with an illustrated anatomy outline including segmental anatomy of the liver, portal venous anatomy, arterial anatomy, biliary anatomy, and hepatic vein anatomy. The reader will also learn about specific biliary complications such as cancers and stones along with options for imaging and repair techniques. A significant portion of the text is devoted to surgical treatment of liver disease and injury.

Biliary Repair Techniques:

- Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- Surgical Approach to Gallbladder Carcinoma

- Surgical Treatment of Mirizzi's Syndrome

- Laparoscopic Management of Common Bile Duct Stones

- Surgical Repair of Bile Duct Injury

Treatment of Liver Disease and Injury:

- Various Techniques for Liver Resection

- Parenchymal Liver Transection

- Surgical Techniques Using Left or Right Hepatectomy

- Laparoscopic Resection of Recurrent Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- Live Donor Transplantation

The printed atlas comes complete with a multimedia DVD and online access to the full text including illustrations and photos, and narrated surgical videos for each chapter.

The multimedia atlas format was designed to showcase the definitive operative procedures, often demonstrated by the surgeons who first developed or refined a technique.

Individual titles are available for purchase. Select one below.

- Surgical Anatomy of the Liver

Christopher B. Hughes, MD - Laparoscopic Intraoperative Ultrasound Guidance During Cholecystectomy

Steven P. Bowers, MD - Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Liver

Mellena D. Bridges, MD - Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Standard Technique and Tips for the Difficult Case

Daniel J. Deziel, MD, FACS - The Surgical Approach to Gallbladder Carcinoma

Matthew J. Weiss, MD; William R. Jarnagin, MD - Laparoscopic Management of Gallbladder Cancer

Xabier de Aretxabala, MD, FACS; Jorge Leon, MD, FACS; Ivan Roa, MD; Nicolas Solano, MD; Juan Hepp, MD, FACS - Laparoscopic Treatment of Mirizzi's Syndrome

Martin Palavecino, MD; Juan Pekolj, MD, PhD, FACS - Laparoscopic Management Options in the Treatment of Common Bile Duct Stones

Augusto C. A. Tinoco, MD, PhD, FACS; Renam C. Tinoco, MD, PhD, FACS; Luciana J. El-Kadre, MD, PhD; Jehovah Guimarães Tavares, MD - Laparoscopic Choledochoduodenostomy for Choledocholithiasis

John Stauffer, MD, FACS; Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS - Laparoscopic Liver Resection for Intrahepatic Biliary Stones

Yifan Wang, MD, PhD; Xiujun Cai, PhD, MD, FACS - Laparoscopic Bile Duct Resection and Hepaticojejunostomy for Type I Choledochal Cyst

Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS; John Stauffer, MD, FACS - Surgical Management of Major Bile Duct Injury

Miguel A. Mercado, MD; Karen Pineda, MD; Artemio García-Badiola, MD - Laparoscopic Resection of Hepatic Cysts

Kimberly M. Brown, MD, FACS; David A. Geller, MD, FACS - Radical Surgery for Hepatic Hydatid Disease

Emilio Vicente, MD, PhD, FACS; Yolanda Quijano, MD, PhD; Carmelo Loinaz, MD, PhD, FACS; Enrique Esteban, MD; Pablo Galindo, MD; Manuel Marcello, MD; Hipolito Duran, MD, PhD; Eduardo Diaz, MD; Alvaro Garcia-Sesma, MD - Parenchymal Liver Transection - Techniques and Devices

Pascal Fuchshuber, MD, PhD, FACS - Ultrasound-Guided Anatomical Segmental Resection with Tattooing

Takuya Hashimoto, MD; Masatoshi Makuuchi, MD - The Hanging Maneuvers

Karim Boudjema, MD, PhD; Damien Bergeat, MD; Laurent Sulpice, MD - Central Hepatectomy

David Nagorney, MD; Daniel Cusati, MD - Reoperative Hepatic Resection

J. Peter A. Lodge, MD, FRCS - Central Hepatectomy with Glisson's Pedicle Transection Method

Ken Takasaki, MD; Satoshi Katagiri, MD; Shunichi Ariizumi, MD; Kotera Yoshihito, MD; Yutaka Takahashi, MD; Masakazu Yamamoto, MD - Laparoscopic Glissonian Technique for Liver Resection

Marcel Autran Cesar Machado, MD, PhD - Non-anatomical Laparoscopic Liver Resection

Emad Kandil, MD, FACS; Ho-Song Han, MD; Saleh A. Massasati, MD; Joseph F. Buell, MD, FACS - Laparoscopy-assisted Donor Right Hepatectomy Employing a Hanging Technique

Go Wakabayashi, MD, PhD, FACS - Laparoscopic Left Lateral Sectionectomy

Marc Mesleh, MD; John Stauffer, MD, FACS; Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS - Laparoscopic Left Hepatic Resection

David A. Geller, MD, FACS; Kiran K. Turaga, MD, MPH; T. Clark Gamblin, MD, MS - Laparoscopic Left Hepatic Trisectionectomy

Aditya Agrawal, MS, FRCS, MD; Brice Gayet, MD, PhD - Extended Left Hepatectomy for Stage III B Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma

Philippe Bachellier, MD, PhD; Pietro Addeo, MD; Daniel Jaeck, MD, PhD, FRCS - Laparoscopic Caudate Lobectomy

Joel Lewin, MBBS; Esteban Sieling, MD; Nicholas O'Rourke, FRACS - Techniques in Purely Laparoscopic and Hand-Assisted Right Hepatectomy

Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS; Michael Parker, MD; John Stauffer, MD, FACS; Ross F. Goldberg, MD - Laparoscopic Right Hepatectomy

Michael D. Kluger, MD, MPH; Sébastien Gaujoux, MD; Daniel Cherqui, MD - Robotic Right Hepatectomy

Gi Hong Choi, MD; Jin Sub Choi, MD - Right Trisectionectomy for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma

Yuji Nimura, MD, FASA (Hon), FESA (Hon), FAFC (Hon) - Laparoscopic Right Posterior Sectionectomy for Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Ho-Seong Han, MD, PhD; Jai Young Cho, MD, PhD; Yoo-Seok Yoon, MD, PhD - Laparoscopic Hepatectomy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Cirrhosis

H. Kaneko, MD, PhD, FACS; Y. Otsuka, MD, PhD - Laparoscopic Left Hepatectomy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in a Cirrhotic Patient

Sasan Roayaie, MD - Laparoscopic Resection of Recurrent Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Giulio Belli, MD; Paolo Limongelli, MD, PhD; Gianluca Russo, MD, PhD; Corrado Fantini, MD; Alberto D'Agostino, MD; Luigi Cioffi, MD; Andrea Belli, MD - Open Hepatic Left Lateral Sectionectomy for Live Donor Transplantation

Tsuyoshi Shimamura, MD; Toshiya Kamiyama, MD, FACS; Satoru Todo, MD, FACS - Technique of Laparoscopic Left Lateral Sectionectomy in Living Donors

Olivier Soubrane, MD - Open Right Hepatic Lobectomy for Living Donor Liver Transplantation

Kyoichi Takaori, MD, PhD, FACS; Koji Tomiyama, MD; Shinji Uemoto, MD, PhD - Extended Liver Resection Following Portal Vein Embolization

John D. Abad, MD; Ching-Wei D. Tzeng, MD; Jean-Nicolas Vauthey, MD, FACS - Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy (ALPPS)

Victoria Ardiles, MD; Fernando Alvarez, MD; Eduardo de Santibañes, MD, PhD

Pietro Addeo, MD

Aditya Agrawal, MS, FRCS, MD

Fernando Alvarez, MD

Victoria Ardiles, MD

Xavier de Aretxabala, MD, FACS

Shunichi Ariizumi, MD

Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS

Philippe Bachellier, MD, PhD

Andrea Belli, MD

Giulio Belli, MD

Damien Bergeat, MD

Karim Boudjema, MD, PhD

Steven P. Bowers, MD

Mellena D. Bridges, MD

Kimberly M. Brown, MD, FACS

Joseph Buell, MD

Xiujun Cai, PhD, MD, FACS

Daniel Cherqui, MD

Jai Young Cho, MD, PhD

Gi Hong Choi, MD, PhD

Jin Sub Choi, MD

Luigi Cioffi MD

Daniel Cusati, MD

Alberto D'Agostino, MD

Daniel J. Deziel, MD, FACS

Eduardo Diaz, MD

Hipolito Duran, MD, PhD

Luciana J El-Kadre, MD, PhD

Enrique Esteban, MD

Corrado Fantini, MD

Pascal R. Fuchshuber, MD, PhD, FACS

Pablo Galindo, MD

T. Clark Gamblin, MD, MS

Artemio Garcí a-Badiola, MD

Alvaro Garcia-Sesma, MD

Sébastien Gaujoux, MD, PhD

Brice Gayet, MD, PhD

David A. Geller, MD, FACS

Ross F. Goldberg, MD

Ho-Seong Han, MD, PhD

Takuya Hashimoto, MD

Juan Hepp, MD, FACS

Christopher B. Hughes, MD

Daniel Jaeck, MD, PhD, FRCS

William R. Jarnagin, MD

Toshiya Kamiyama, MD, FACS

Emad Kandil, MD, FACS

Hironori Kaneko, MD, PhD, FACS

Satoshi Katagiri, MD

Michael D. Kluger, MD, MPH

Jorge Leon, MD, FACS

Joel Lewin, MBBS

Paolo Limongelli, MD, PhD

J. Peter A. Lodge, MD, FRCS

Carmelo Loinaz, MD, PhD, FACS

Marcel Autran C. Machado, MD, PhD

Masatoshi Makuuchi, MD

Manuel Marcello, MD

Saleh A. Massasati, MD

Miguel A. Mercado, MD, FACS

Marc G. Mesleh, MD

David M. Nagorney, MD

Yuji Nimura, MD, FASA (Hon), FESA (Hon), FAFC (Hon)

Nicholas O'Rourke, FRACS

Yuichiro Otsuka, MD, PhD

Martin Palavecino, MD

Michael Parker, MD

Juan Pekolj, MD, PhD, FACS

Karen Pineda, MD

Yolanda Quijano, MD, PhD

Ivan Roa, MD

Sasan Roayaie, MD

Gianluca Russo, MD, PhD

Eduardo de Santibañes, MD, PhD, FACS

Tsuyoshi Shimamura, MD

Esteban Sieling, MD

Nicolas Solano, MD, FACS

Olivier Soubrane, MD

John Stauffer, MD, FACS

Laurent Sulpice, MD

Kyoichi Takaori, MD, PhD

Yutaka Takahashi, MD

Ken Takasaki, MD

Jehovah Guimarães Tavares, MD

Augusto C. A. Tinoco, MD, PhD, FACS

Renam C. Tinoco, MD, PhD, FACS

Koji Tomiyama, MD

Satoru Todo, MD, PhD

Kiran K. Turaga, MD, MPH, FACS

Ching-Wei D. Tzeng, MD

Shinji Uemoto, MD, PhD

Yoo-Seok Yoon, MD, PhD

Jean-Nicolas Vauthey, MD, FACS

Emilio Vicente, MD, PhD, FACS

Go Wakabayashi, MD, PhD, FACS

Yifan Wang, MD, PhD

Matthew J. Weiss, MD

Masakazu Yamamoto, MD

Kotera Yoshihito, MD

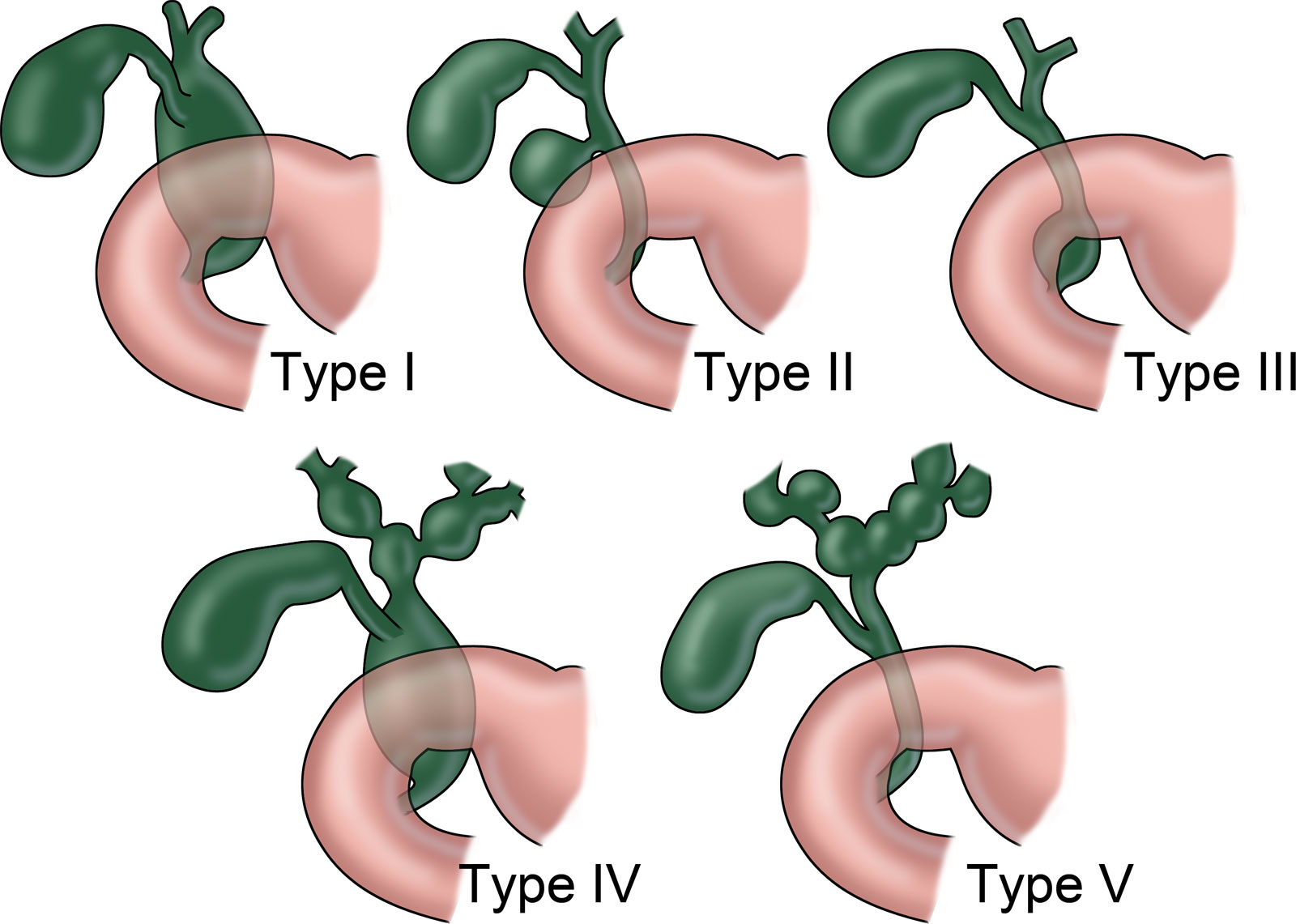

Choledochal cysts are cystic dilatations of the biliary tree with a 4:1 female preponderance and are typically a surgical problem of infancy or childhood. However, in nearly 20 percent of patients, the diagnosis may be delayed until adulthood. Choledochal cysts are classified into five main types. (Figure 1) Type I choledochal cysts are solitary fusiform dilatations of the entire common hepatic and common bile ducts (CBDs) and represent 80-90% of these lesions. The risk of subsequent malignant transformation mandates complete excision of the entire dilated extrahepatic biliary tree from the confluence down to the pancreaticobiliary duct junction. Reconstruction is performed by a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. The traditional operative approach was via an open approach, but a minimal-access approach for this operation has been performed successfully with good outcomes. We herein present our technique of laparoscopic bile duct resection and hepaticojejunostomy for Type I choledochal cysts.

Anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction (APBDJ) is an anatomical abnormality commonly seen in patients with choledochal cysts and has been hypothesized to be a cause of cystic degeneration of the bile duct due to reflux of pancreatic juice. However, APBDJ is not always present, and other causes such as hereditary factors and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction may play a role in the development of choledochal cysts. Regardless, preoperative imaging of the biliary tree is mandatory for all patients prior to cyst excision to rule out impacted stones, neoplasm, or APBDJ with the potential to damage the pancreatic duct. Direct cholangiography may be obtained prior to surgery by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) or at the time of surgery via intraoperative cholangiography (IOC). However, the preferred and most noninvasive imaging modality is MRI cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), as this allows for delineation of the biliary tree and the display of additional potentially relevant anatomical information.

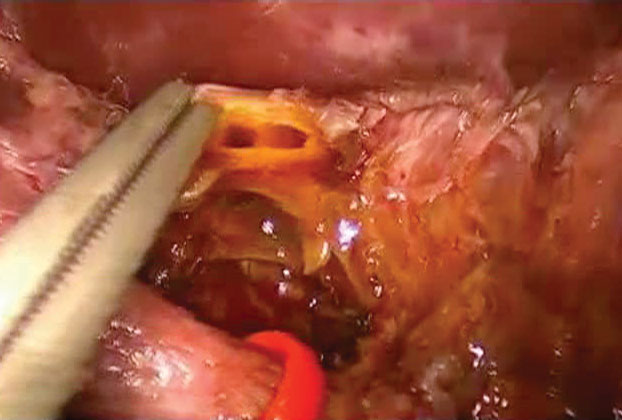

Operative goals include complete excision of the cyst and require excision of the distal CBD below the cyst, often immediately above or in its proximal portion within the head of the pancreas proximal to its junction with the pancreatic duct to prevent narrowing or injury to the pancreatic duct. Proximally toward the liver, the cyst is mobilized to the ductal confluence where it is transected. Occasionally, the cystic dilatation may extend above the bifurcation and require excision of the biliary confluence. Biliary-enteric flow is reestablished through a retrocolic duct to mucosa Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Positioning of the arteries below the anastomosis may facilitate an easier anastomosis and reduces potential injury in case of reoperation.

Instrumentation, patient position and operating room (OR) setup, and trocar placement are described here.

Instrumentation

- 30 and 45 degree laparoscope

- 5 mm / 10 mm atraumatic graspers, DeBakey type

- 5 mm fine graspers

- Finger-type articulator retractor

- 5 mm laparoscopic needle drivers and/or pediatric surgery fine drivers for small duct anastomosis

- 5 mm liver retractor

- Maryland grasper, shears/scissors

- Energy/vessel sealing device

- Bipolar cautery

- Laparoscopic articulating linear stapling devices (30, 45, 60 mm cartridges with 2.5, 3.8, and 4.5 mm staples)

- Laparoscopic ultrasound probe

- Suction irrigator

- Laparoscopic bag retrieval system

- 5 mm and/or 10 mm clip appliers

- Vessel loops, endoloop

- Various sutures that may include braided and nonbraided absorbable suture varying from 3 to 5-0 depending on use (sutures are usually cut 15 cm to 18 cm in length)

- Bulldog and vascular clamps

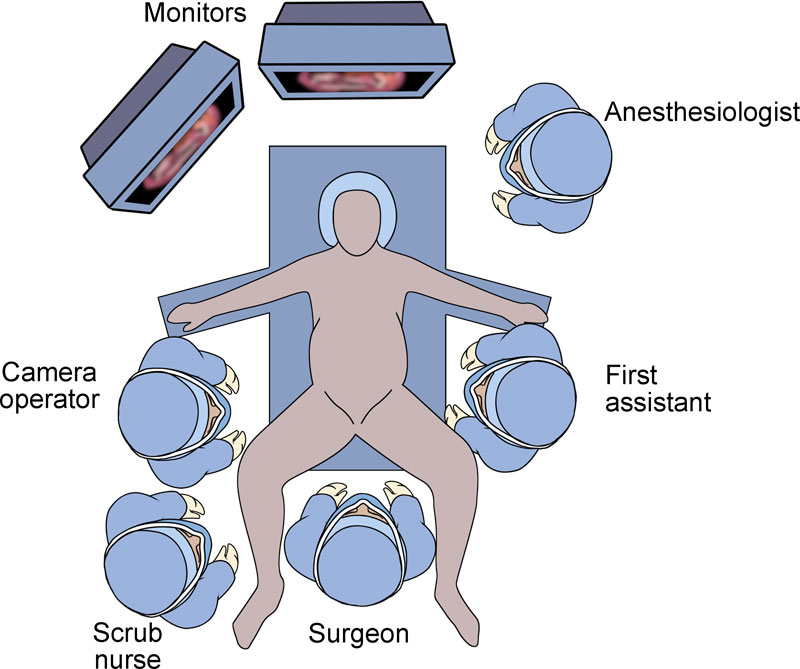

Patient Position and OR Setup

The patient is placed in a supine position with both arms out. A roll is placed under the right flank to elevate the right subcostal region. All pressure points are padded, and the patient is well secured to the table. Generally, 3 inch silk tape and/or safety straps are placed across the patient's chest, pelvis, and legs to avoid slippage during the procedure. Maximum left-to-right tilting as well as full Trendelenburg and reverse Trendelenburg positions are performed on the undraped patient to visually confirm the security of the positioning prior to prepping or draping.

The patient is placed in a supine position with both arms out. A roll is placed under the right flank to elevate the right subcostal region. All pressure points are padded, and the patient is well secured to the table. Generally, 3 inch silk tape and/or safety straps are placed across the patient's chest, pelvis, and legs to avoid slippage during the procedure. Maximum left-to-right tilting as well as full Trendelenburg and reverse Trendelenburg positions are performed on the undraped patient to visually confirm the security of the positioning prior to prepping or draping.

- Anesthesiologist

- Scrub nurse

- Camera operator

- First assistant

- Monitors (2)

- Surgeon

- Cautery (bipolar/monopolar), energy device system

- Sequential compression stockings

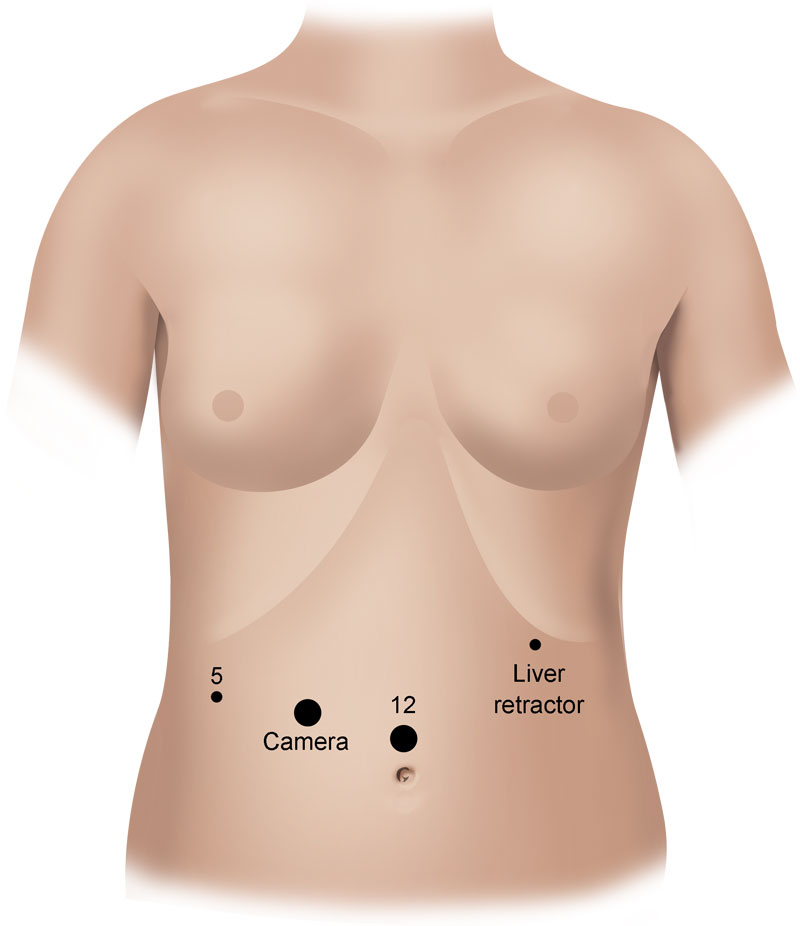

Trocar Placement

The size and number of trocars can be varied according to patient's body habitus and angle needed for exposure. In general, the surgeon should have a general plan, but trocars can be added or changed to a larger size as needed. Similarly, the camera site and the side of the table on which the surgeon stands should be constantly assessed and changed as needed for better exposure or to facilitate a certain task. In general, the following is the most standard configuration: A 12 mm supraumbilical Hasson trocar; a high right lateral subcostal 5 mm trocar; a right hemiabdomen 12 mm trocar; a high left subcostal midaxillary 5 mm trocar. Additionally, a left hemiabdomen 5-mm trocar can be placed for an assistant.

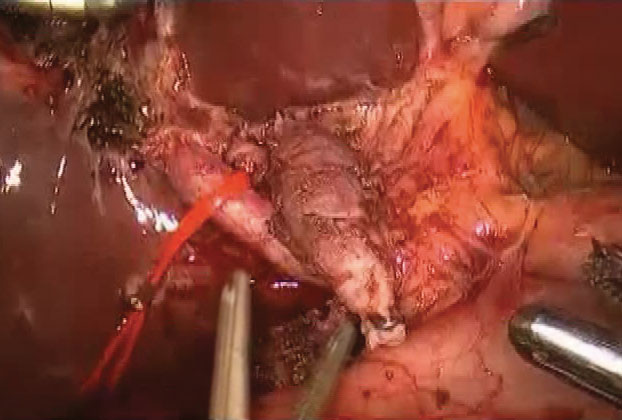

Dissection begins in the right upper quadrant. Often, the patient has either had a prior cholecystectomy or has had inflammation related to the choledochal cyst, making identification and isolation of the common bile duct difficult. Careful dissection of the structures in the hepatic hilum allows the surgeon to separate the duct from the medially located artery and the posterior portal vein. The duct is then followed into the head of the pancreas to allow for complete distal division. Once divided distally, the duct is freed, allowing its gradual dissection from the neighboring structures of the hepatoduodenal ligament while retracting it superiorly, anteriorly, and to the sides. This allows for dissection under direct visualization, particularly on the posterior plane of the duct. Proximal division is similarly performed above the involved portion of the duct. If necessary, and for the most part in the presence of a large cyst, the cyst can be opened anteriorly prior to its proximal division to clearly assess the needed extent of dissection and to choose the site for proximal division.

A complete excision of the cyst is usually advised, but some authors advocate leaving a 1 mm rim of the cyst wall proximally when a wide anastomosis is not feasible if complete cyst excision is performed.

Studies have shown that laparoscopic liver surgery is a safe and effective approach for the management of surgical liver disease in selected patients in the hands of trained surgeons.1-4 However, most procedures are limited resections, and only 9 percent of nearly 3,000 cases reported in the international literature were right hepatectomies (segments V-VIII).5 The laparoscopic right hepatectomy remains a challenging procedure.

After a brief discussion of patient selection and necessary devices, we describe the technical aspects of the laparoscopic anterior approach to right hepatectomy in three stages:

- Positioning; port placement; inspection of the peritoneal cavity and liver; ultrasonography

- Approach; pedicle control; anterior liver mobilization; hilar plate dissection

- Marking the liver; parenchymal dissection, hemostasis, and bile duct ligation; specimen extraction; cholangiography, drainage, and closure.

Location and, to a lesser extent, lesion size are the most important determinants of when laparoscopic resection is appropriate. In the case of right hepatectomy, we recommend lesions without connections to the liver hilum, the main hepatic veins, or the inferior vena cava.

We consider large tumors (ie, >8 cm) a relative contraindication to a laparoscopic approach. Other relative contraindications include gallbladder cancer and hilar cholangiocarcinoma. An open procedure is used when a need exists for complete vascular occlusion, when oncologic principles could be better served via laparotomy, or when medical conditions that contraindicate a prolonged pneumoperitoneum are present.

High-quality imaging with vascular reconstruction is necessary to understand the patient's intrahepatic arterial, portal, and biliary anatomy. A careful review should be performed before proceeding to the operating room.

The Laparoscopic Operating Room

- All laparoscopic equipment must be state-of-the-art and in good working order, and staff should be familiar with the proper setup and functioning of the equipment.

- An adjustable, remote-controlled, electric split-leg table is needed.

- Monitors are placed lateral to each shoulder with a hanging monitor above the patient's head.

- One or two CO2 insufflators are required to maintain a pneumoperitoneum of 12 mm Hg.

- Ultrasound with B- and D-modes and a high-frequency laparoscopic transducer are necessary.

- An energy vessel sealing device is essential.

- An ultrasonic dissector device is required.

- A set of conventional instruments and retractors for open surgery should be readily available in case emergency conversion is required.

Necessary Laparoscopic Instruments

- 10 mm 30 degree laparoscope

- Atraumatic bowel graspers

- Curved and right angle dissectors

- Scissors

- Needle drivers

- Liver retractor

- Bipolar diathermy forceps

- Monopolar diathermy hook

- Articulated linear stapler (30 mm and 45 mm vascular cartridges)

- Suction irrigator

- An umbilical tape and a 4-6 cm 16-Fr rubber tube to serve as a tourniquet

- Titanium clip applier (small and medium)

- Plastic locking clip applier (medium and large)

- Endoscopic bag

- 5-0 monofilament sutures cut to 20-30 cm

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position with the lower limbs apart on a split-leg table. The right arm is padded and tucked at the side. The surgeon stands between the legs with an assistant seated at each side. (Figures 1 and 2) The left assistant can be replaced by an adjustable instrument holder. The scrub nurse and instruments are positioned lateral to the right leg or behind the surgeon. A Mayo stand positioned over the right leg holds the most commonly utilized instruments. Reverse Trendelenburg allows the bowels to drop into the lower abdomen, and the table is tilted laterally as necessary to take advantage of gravity and the weight of the liver to improve exposure.

Port Placement

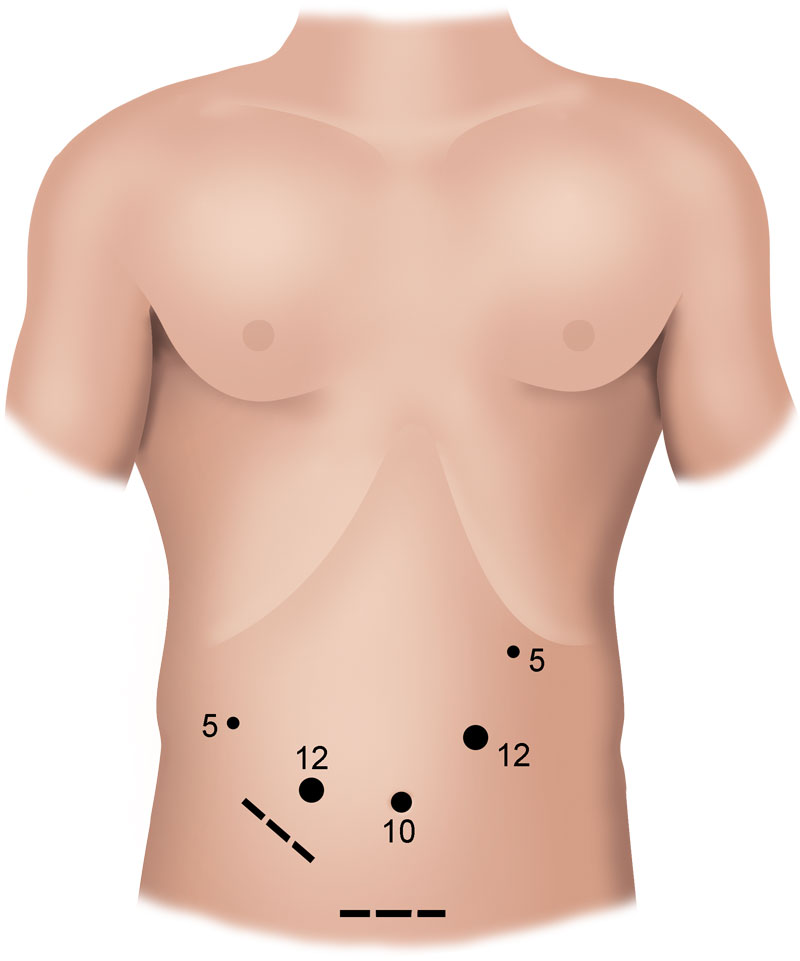

5 trocars are placed: (Figures 3 and 4)

- 1 x 10 mm port is placed in the umbilicus or supraumbilically for the camera.

- 2 x 12 mm paramedian ports are the working ports.

- 2 x 5 mm lateral ports are used for retraction.

The open technique is used to insert the camera port, and the remaining four ports are placed under direct vision generally following the profile of the liver in a curve from right to left.

Inspection of the Peritoneal Cavity and Liver and Ultrasonography

A thorough inspection of the peritoneal cavity for carcinomatosis and the liver for signs of superficial lesions, steatosis, cholestasis, cirrhosis, or other gross pathology is performed. Laparoscopic ultrasonography of each segment is conducted to confirm the location of the lesion and assess the vascular anatomy.